By Paul V. Harrison

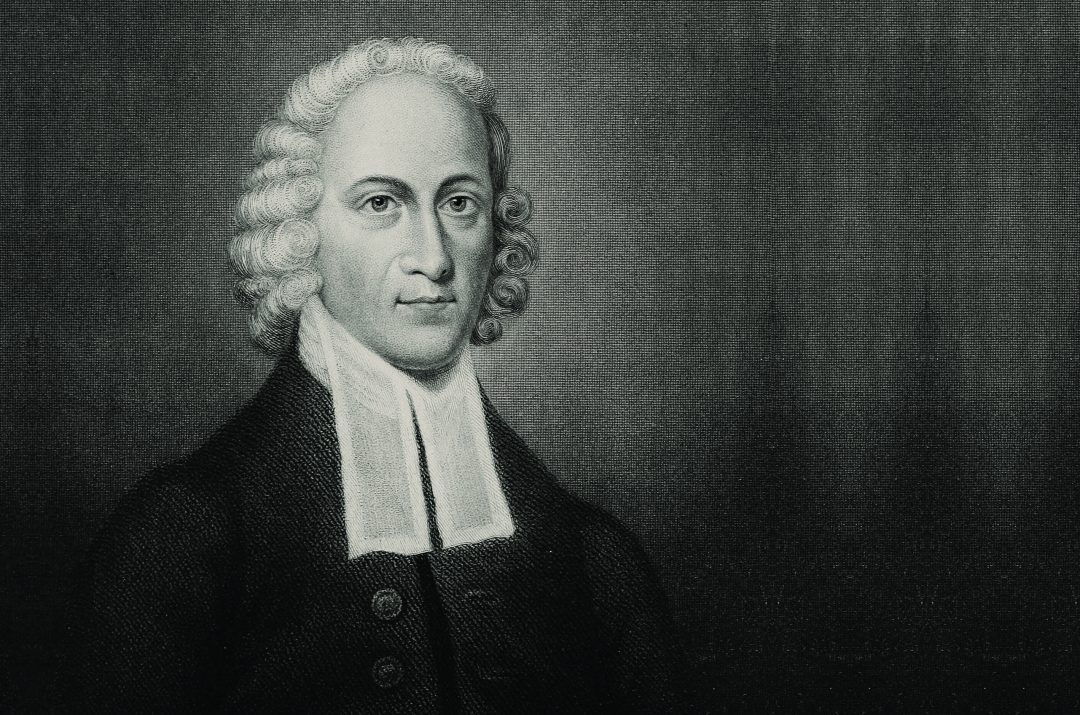

Outside of Scripture, I’ve never read better sermons than those delivered by Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758). My favorite is “The Excellency of Christ,” preached in August 1736. He chose Revelation 5:5–6 as his text: “Weep not: behold, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, the Root of David, hath prevailed to open the book, and to loose the seven seals thereof. And I beheld, and lo in the midst of the throne…stood a Lamb, as it had been slain.”

Focusing on Jesus’ identity as Lion and Lamb, Edwards asserted: “There is an admirable conjunction of diverse excellencies in Jesus Christ.” He explained: “There do meet in Jesus Christ infinite highness and infinite condescension,” “infinite justice and infinite grace,” “infinite glory and lowest humility,” “infinite majesty and transcendent meekness,” “infinite worthiness of good, and the greatest patience under sufferings of evil,” “absolute sovereignty and perfect resignation,” “self-sufficiency, and an entire trust and reliance on God.”

Much went into shaping Edwards. He grew up in a preacher’s home, graduated from Yale, and became pastor of the Congregational church in Northampton, Massachusetts, where his grandfather Solomon Stoddard served 60 years. Edwards ministered to this flock for about 24 years, seeing hundreds of conversions during a movement known as the Great Awakening. In spite of this, his congregation eventually fired him for perceived aberrant theology. After a short stint as a missionary to Native Americans, he accepted the presidency of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton), only to die a few months later at age 54 of a smallpox inoculation gone bad.

While most only know him for his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” the Yale edition of his works fills 26 large volumes. No American theologian made a more significant impact on Christianity than Edwards, and his preaching was no small part of that.

Godliness

What made Edwards a powerful preacher? First, his genuine godliness gave force to his words. From his youth, he followed hard after God. As a teenager he penned 70 resolutions, the first of which read: “Resolved, That I will do whatsoever I think to be most to the glory of God, and my own good, profit, and pleasure, in the whole of my duration.” Number 5: “Resolved, Never to lose one moment of time, but to improve it in the most profitable way I possibly can.” Number 19: “Resolved, Never to do any thing, which I should be afraid to do, if I expected it would not be above an hour before I should hear the last trump.”

Edwards spent much time in prayer and Bible study. The beauties of nature reminded him of the Creator. Thunder and lightning made him mindful of God’s majesty and sovereignty. An informed conscience guided his lifestyle. He devoted himself to his wife and 11 children. He made anonymous gifts to the needy. In short, he lived in the self-conscious spotlight of God and His Word. Such living adds much to a preacher’s words.

Preparation

Second, Edwards’ sermons reflected careful preparation. He recognized the scriptural requirement to be “apt to teach” meant he had to give himself tirelessly to study. He began most days at four or five in the morning. Before his head hit the pillow most nights, he had spent 13 hours in study. You can only preach what you know, so Edwards worked to know much about God and Scripture. This was not knowledge for its own sake, but to deepen his relationship with God and to share his findings with his flock. That sharing generally took the form of extended sermons, written word-for-word, which he would quote and read to his people. He followed the pattern of preaching in his day: explanation of the text, development of the doctrine there, and an extended application. He usually prepared three, hour-long sermons each week. Around 1,200 of these works have survived.

I can just hear the objections being voiced: “Nobody should study that long.” “People won’t listen to that kind of preaching today.” “Others have preached with power who didn’t take such pains in study.” Personally, I relate to these objections and agree somewhat. However, when much academic slothfulness abounds and is evident in our pulpits, we need to be pulled back in the direction of more study. A seasoned minister once told me preaching was the easiest part of pastoring. Edwards would not have agreed.

Scripture-Centered

Third, the sermons of Jonathan Edwards were powerful because of their heart-searching, scriptural focus. He always took a text and trained his attention on what God was saying. What did He mean? What did the text teach about God and mankind? How did it apply to life?

For example, in his sermon on Luke 17:32, “Remember Lot’s Wife,” Edwards said: “Some in Sodom may seem to carry a fair face, and make a fair outward show; but if we could look into their hearts, they are every one altogether filthy and abominable.” Drawing from Genesis 19:23, he warned, “It seems to have been a fair morning in Sodom before it was destroyed.”

His application focused on those still in their sins: “Sodom is the place of your nativity…You are the inhabitants of Sodom…Remember Lot’s wife, for she looked back, as being loth [sic] utterly and for ever to leave the ease, the pleasure, and plenty which she enjoyed in Sodom, and as having a mind to return to them again; remember what became of her—Remember the children of Israel in the wilderness, who were desirous of going back again into Egypt…You must be willing for ever to leave all the ease, and pleasure, and profit of sin, to forsake all for salvation, as Lot forsook all, and left all he had, to escape out of Sodom.”

This kind of heart focus was how Edwards always preached.

Logical

Fourth, his sermons were powerful because they pressed his listeners with unrelenting logic. While Edwards had no qualms about stirring emotions, he led his people to grapple with truth. Acts 18:4 says Paul “reasoned in the synagogue every Sabbath.” Edwards followed Paul’s example and was always pressing his congregation to think, believing clear thinking would reveal truth and impress it on hearts.

For example, in his sermon on 1 Kings 18:21, where Elijah challenges the people torn between two opinions, Edwards put forth the following doctrine: “Unresolvedness in religion is very unreasonable.” He stated: “There are but two things which God offers to mankind for their portion: one is this world, with the pleasures and profits of sin, together with eternal misery ensuing; the other is Heaven and eternal glory, with a life of self-denial and respect to all the commands of God. Many, as long as they live, come to no settled determination which of these to choose. They must have one or the other, they cannot have both; but they always remain in suspense, and never make their choice.”

When a man speaks from his core beliefs, when he stakes his soul and all he has on the truth of his message, and when what he says is indeed properly aligned with the truth of Scripture, there is inherent power in the words.

Edwards proceeded to show how unreasonable it was to follow such a course of indetermination. It’s unreasonable because religion is the thing most important to us. “It makes an infinite difference to us.” It’s unreasonable because the issues of choosing God or not are fully within our ability to understand. “God hath made us capable of making a wise choice for ourselves.” Additionally, “God puts into our hands a happy opportunity to determine for ourselves…God setteth life and death before us.”

The onslaught of reason did not let up: “The things among which we are to make our choice are but few in number; there are but two portions set before us…If there were many terms in the offer made us, many things of nearly an equal value, one of which we must choose, to remain long in suspense and undetermined would be more excusable; there would be more reason for long deliberation before we should fix. But there are only two terms, there are but two states in another world, in one or the other of which we must be fixed for all eternity.”

Edwards’ last point states: “Delay in this case is unreasonable, because those who delay know not how soon the opportunity of choosing for themselves will be past.”

Oratory

Fifth, power accompanied Edwards’ preaching because of his delivery. Unlike his contemporary George Whitefield, Edwards was not known for being dramatic. In fact, he almost always carried a full manuscript to the pulpit and read most of it to his congregation. But as counterintuitive as it may seem, his deliberate, thoughtful delivery carried power.

His friend Samuel Hopkins described Edwards’ sermon delivery as “easy, natural, and very solemn. He had not a strong, loud voice; but apperar’d [sic] with such gravity and solemnity, and spake with such distinctness, clearness, and precision; his Words were so full of Ideas, set in such a plain and striking Light, that few Speakers have been so able to demand the Attention of an Audience as he.” Hopkins added the preacher’s words often revealed “a great degree of inward fervor, without much noise or external emotion.”

Bold

Finally, Edwards’ sermons were powerful because he spoke them boldly as the truth of God. He maintained that when one listened to Scripture rightly presented, he heard, as it were, the voice of God. In this connection he insisted that real reliance on God and His Word meant that everything, even longstanding church tradition, had to be evaluated in light of Scripture. He wrote: “Surely it is commendable for us to examine the practices of our fathers; we have no sufficient reason to take practices upon trust from them. Let them have as high a character as belongs to them; yet we may not look upon their principles as oracles…He that believes principles because they affirm them, makes idols of them.”

Since the mid-1600s New England Congregationalists had by-and-large accepted the Lord’s Supper should be served to morally upright church attenders, “visible saints,” as they were called, even if they couldn’t assert they had been converted. It was believed, especially by Edwards’ Grandfather Stoddard, God would make the Supper a “converting ordinance.” Among the justifications for this practice, Congregationalists pointed to God’s broad command to the Old Testament people of God to participate in the Passover. Additionally, believing in infant baptism, Congregationalists thought babies of these “visible saints” should be baptized.

Edwards inherited these practices and went along with them for many years on the force of his grandfather’s arguments and reputation, having learned them as a child. But in maturity, Edwards concluded the practices were unscriptural. This laid him “under an inevitable necessity publicly to declare and maintain” his new position. This stand took courage, for, as he wrote to a friend, “this will be very likely to overthrow me, not only with regard to my usefulness in the work of the ministry here, but everywhere.” His congregation, in fact, did turn on him and fired him. The point for us, however, is that Edwards’ preaching carried power because he boldly presented God’s truth over tradition.

Edwards helps us see the truth about sermons. In God’s hands, they can be used to transform souls. When a man speaks from his core beliefs, when he stakes his soul and all he has on the truth of his message, and when what he says is indeed properly aligned with the truth of Scripture, there is inherent power in the words.

About the Writer: Dr. Paul Harrison has pastored Madison FWB Church (AL) since 2015. Previously, he served as pastor of Cross Timbers FWB Church (TN) 22 years. He taught church history and Greek at Welch College 17 years, and has served as both assistant editor and editor for Integrity theological journal. He is creator of Classic Sermon Index, a subscription-based online index of nearly 60,000 sermons. Clients include Harvard, Baylor, and Vanderbilt universities among others. He and his wife Diane have two sons and three grandchildren.

< Return to PULP1T Magazine | Fall 2018